My name is Peter, but most of my friends don’t call me that. Somewhere in the murky waters of ninth grade, many of my friends started calling me “Peetah”. By no suggestion of my own, my name had changed into its phonetic pronunciation from across the pond. The reason for this switch is simple.

To us Americans, phrases like “Peter”, “Harry!”, “Rubbish”, and “Hello, Governor!” are infinitely more fun to say when said in a British accent.

As someone who has always done impressions and voices well, I have seen firsthand the ridiculous obsession many Americans have with British accents. I was flocked, in grade school, anytime I told Malfoy to give it here, or I’d knock him off his broom. In seventh grade science, I despised a temporary substitute teacher enough, within the first few moments of hearing him talk, to speak strictly in a British accent for the next three weeks. I took two things away from that experiment. I learned not only that “Sickle cell” is very hard to say in a British accent, but that if you constantly lie to someone about your personality for three weeks, they won’t be very happy with you when they’re your full time teacher the next year. Thank goodness for the memory of the look on his face when I first broke character. Ah, was I ever a cheeky little bugger. Years of entertaining others with British catchphrases has been a fun ride, but it has left me with one conclusion about the relationship between Brits and Americans that I don’t very much like.

Americans, for the most part, fail to recognize that there is more than one accent from the country of England.

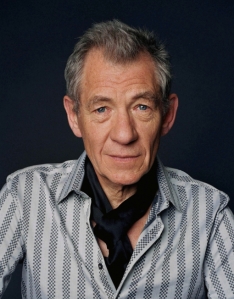

They deny the existence of any British voice outside of what they hear on television. When speaking with the average American, dialects one might find in Liverpool or Birmingham are ignored, and Cornish and Suffolk might as well have never existed. Cockney, thanks to Oliver Twist and Bellatrix Lestrange, has remained comical. But, because of the rise of international media in recent years, the Queen’s English (what is heard on BBC) is, exclusively, the voice of Great Britain which Americans hear and accept. In essence, most people in America associate a British accent with the voice – and demeanor – of Sir Ian McKellan.

For English folk, this gigantic generalization can be a good thing. They benefit from American ears, which associate the accent they hear with positive things like knowledge, high class, and sophistication. When an American hears an English accent, they think of all the posh and well-educated characters they have ever seen on television or in the movies. The antithesis of my Ian Mckellan statement, however, is much less satisfying.

If Americans listen to an English accent and hear Ian McKellan, the quintessential Brit, then who is the quintessential American? Who do British people hear when they listen to an American accent?

If Brits, or people of any nationality, for that matter, hear John Wayne when I speak, I think I might take a vow of silence. Nothing against the Duke, but I don’t roll my own cigarettes or swig whiskey. In fact, I don’t roll anyone’s cigarettes and I don’t think I’ve ever swigged anything, and assume those characteristics based on my voice would butcher the truth.

If a stereotypical British accent implies knowledge, then a stereotypical American (or Australian) accent implies ignorance. Since a general English voice brings to mind high-class, one can infer that an American voice rings of classlessness. Where sophistication is found in one accent, impulse and crass are found in the other.

In light of American society’s ridiculous associations and assumptions, resurrecting that seventh grade identity for the duration of my children’s development phases has never seemed like such a good idea. It’s for their own good.